Offensive rebounding is a different beast nowadays. As Bobby Manning wrote this weekend, crashing has become part of Joe Mazzulla’s strategy. It’s a hedge against poor shooting nights; an effort to add more possessions overall to the pot so volume, if nothing else, can lead to more points on the board.

The Celtics are grabbing 10.3 offensive rebounds per game, but in 2023, that doesn’t mean it’s just the bigs crashing and doing big man things. Jrue Holiday leads the Celtics in offensive rebounds with 31 (he’s also second in defensive rebounds, by the way, and is Boston’s second-leading rebounder behind Jayson Tatum with 7.2 per game). In fact, Holiday and Payton Pritchard account for one more offensive rebound (50) than Al Horford and Kristaps Porzingis (49).

Yeah, Porzingis has missed a couple of games, but the point stands. Guards are just as important as the bigs when it comes to keeping possessions alive and adding more bites at the apple to score some points.

The Celtics have 196 offensive rebounds this season, 71 of those belong strictly to guards (Holiday, Pritchard, Derrick White, Dalano Banton, Svi Mykhailiuk) and it’s 87 if you throw in Sam Hauser, who is exclusively a perimeter player. If you want to throw in Jaylen Brown, who mills around the baseline but is clearly not a big, then it’s 97.

That's a lot of guards getting in there doing what used to be a big man’s work.

“I came into an era where I couldn't take rebounds from bigs,” Holiday told Boston Sports Journal. “If I got a rebound from a big, my teammate was messing me up.”

Nowadays, bigs welcome that help, especially since they're asked to do more than bigs in the past. Porzingis is involved in actions up around the free-throw line and 3-point line. That sometimes leaves opportunities for guards like Holiday to sneak in for offensive rebounds.

And with the sheer volume of 3-pointers taken, that leaves more long rebounds available for guards to swoop in and grab. A lot of offensive rebounds for guards can simply be front or back-rim misses that soar over the top of all the bigs and drop gently into their hands like one of those parachute drop promotions at The Garden.

But then there's the corner crash. Guards who have spotted up in the corner crashing to the hoop to take advantage of a slight opening and maybe get a putback. The most famous such play happened in Game 6 of the Eastern Conference Finals last season when White put back a Marcus Smart miss to force Game 7.

The corner crash is a little bit like a game of poker or blackjack. You need to be able to recognize the situation, make your bet on what the right move is, and then hope for a little luck to come your way. You don’t always win, but if you do it right and you’re good enough at it, you can win enough to make it worth it.

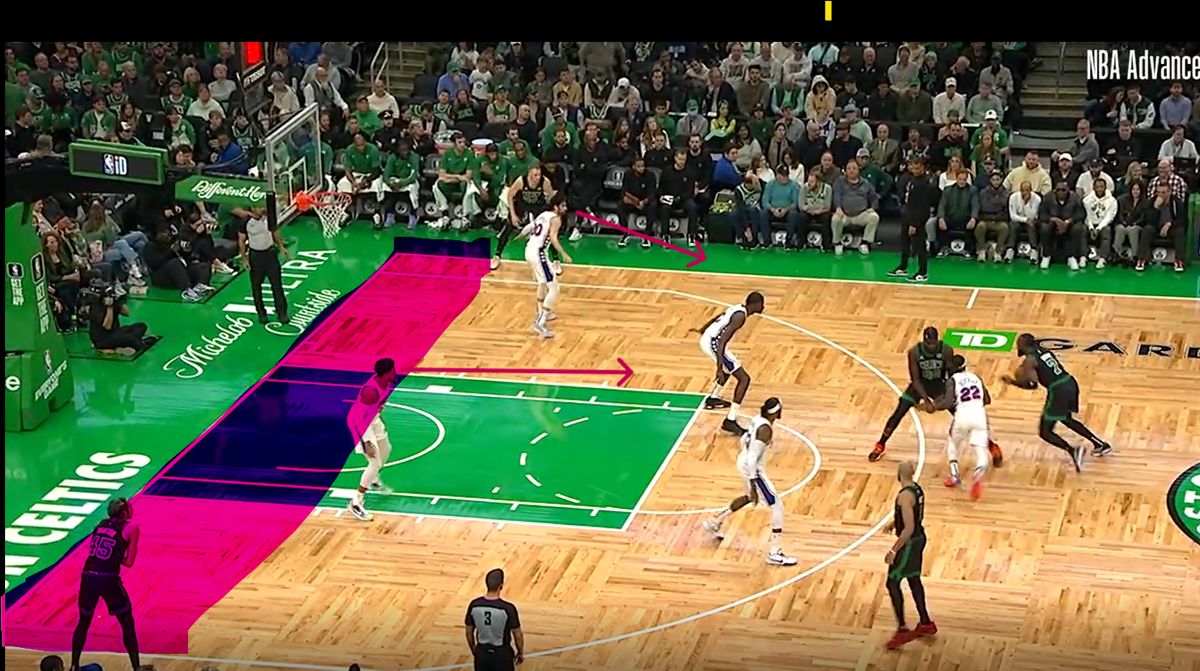

One good recent example comes from Banton against the Sixers.

You can see how much room the guys in the corner have to work with.

Unless a defensive rebounder is focused on the box out, there's a lot of room to maneuver down on the baseline. With Tobias Harris ball-watching, Banton is free to get to a good rebounding spot. And with Brown on the right side of the floor, there's a statistically better chance of the rebound going long the opposite way, so being on the left side gives you better odds of grabbing the rebound.

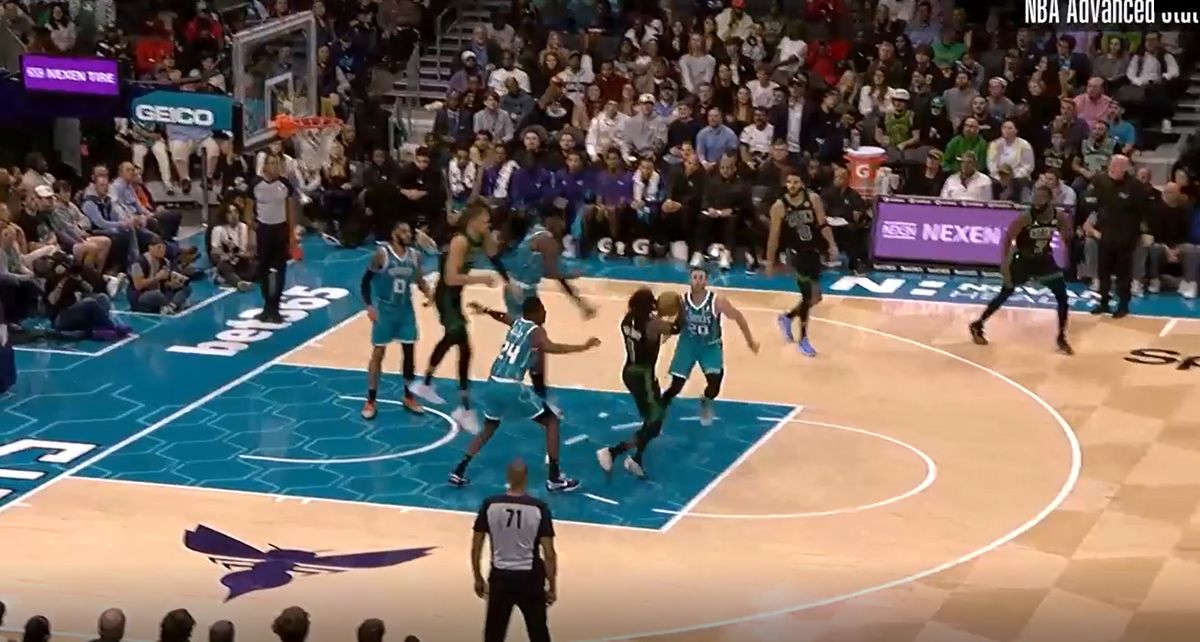

Sometimes crashing from the corner just means going to an open spot and hoping to get a little lucky. In this play, Luke Kornet is being boxed out on the left side but still has a chance at a tip to keep the ball alive. Pritchard uses the box out as a sort of screen to get to an open spot on the right, and he just happens to be in a good spot for the rebound.

“Yeah, (it’s) a little bit (like gambling),” Holiday said. “With a little bit of awareness. With a little bit of feel. But yeah, it definitely is a gamble.”

The feel and the awareness come into play when a guy like Holiday reads the situation. Going from the corner doesn’t always mean ending up on a baseline spot. Sometimes a man in the corner has another route to take based on what he sees on the floor and where the shot is taken.

“A lot of time I try to see if my man is either looking at me or not, depending on what angle I take or how quickly I go,” Holiday told BSJ. “Honestly, it’s just about going. I think being consistent, going to the basket because you’ll get a few of them.”

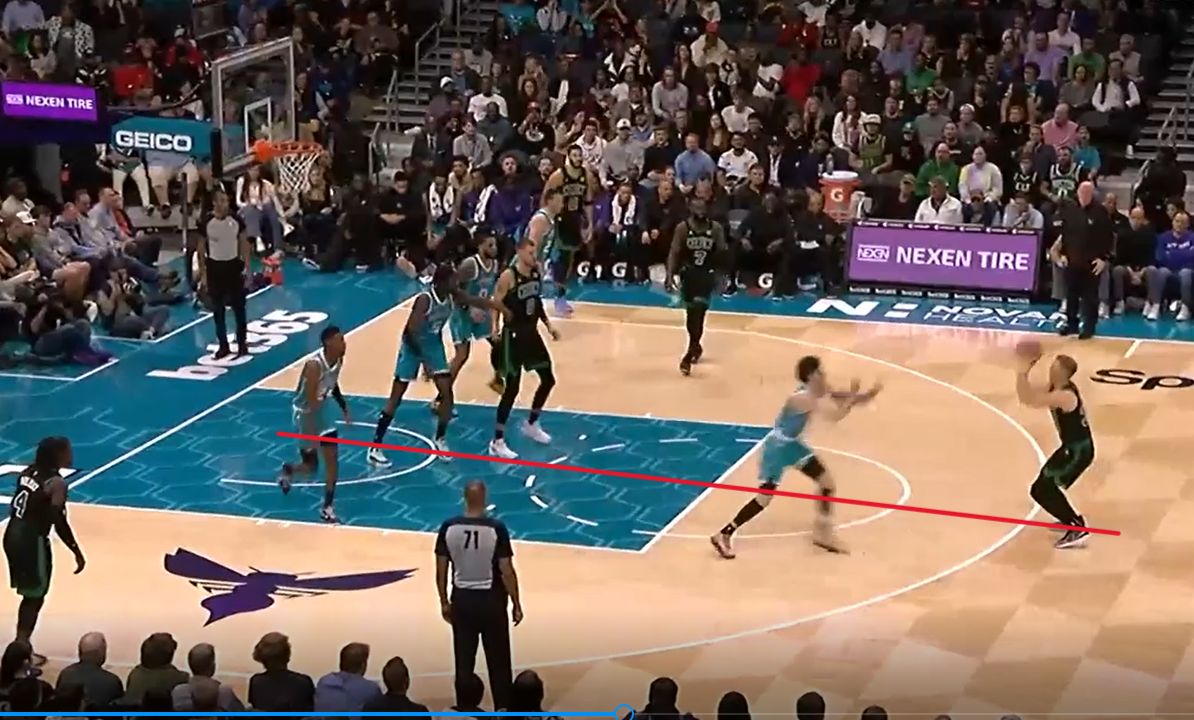

Here, Holiday has the choice to go baseline on the corner crash, but Hauser is basically shooting from the top of the key. Again, rebounders generally assume the ball is going long off the rim. On a basically straight-on 3-point shot, there's a good chance a rebound will come to the middle of the floor. So let’s draw a straight line down the floor.

Here is where Holiday goes.

Right on the line. Awareness and feel.

“I think it's a feel, finding gaps, being able to kind of read where the ball comes off the rim,” Holiday said. “I think just with time and playing basketball, a lot of times you can kind of see it in the air if the ball is off or whatever, you kind of see if it's gonna hit a back rim or side rim or whatever. Sometimes you're just lucky and you're in the right place at the right time.”

Let’s go back to the beginning of this all, and the concept of offensive rebounding in general. It was abandoned in favor of getting back, but that happened at a time before the corner 3-pointer became the most important shot in basketball. Now, guards camp out in the corners hoping to get a chance at the highest-value shot in the game. They don’t always come, but now they're in unique position to not only try to rebound, but also get back if they don’t.

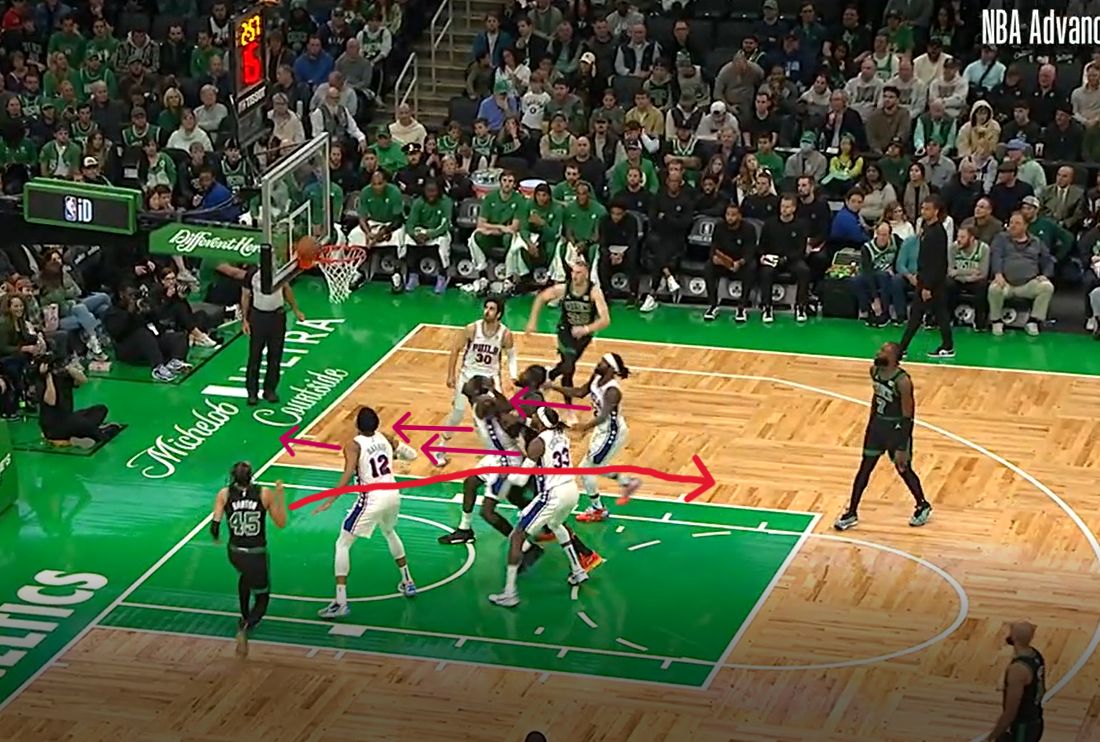

Let’s go back to that Banton corner crash. Look at where he is and where his momentum is going in relation to the Sixers.

He’s running in from the corner. He’s on the move. Four Sixers are facing the basket, which means if they are actually able to secure the rebound, they have to stop, plant, turn, and run in the other direction.

Well, Banton is already running, and his momentum can carry him through the play and back on defense without getting caught flat-footed.

“I think it's more of like a flow,” Holiday told BSJ. “If I come from the corner and kind of go toward that free throw line I can kind of still run back and I'm in a good position to run back. Usually when you box out or usually when you crash offensively, you're behind guys. So I know that the person who's going to be an offense is in front of me, potentially, so I can turn around see ball, see man.”

Nearly 200 offensive rebounds means scores of opportunities to score again. The old-school philosophy of abandoning the offensive glass has given way to a different mentality, especially in Boston, and a lot of that is driven by guards. The wide-open nature of the game and the planting of shooters in the corners has created new opportunities that weren’t really there in the past. "Corner crash" is a relatively new entry into the basketball lexicon, and it’s a result of the modern way of playing the game. When a team has guards that are good at it like Boston does, it can lead to the extra points and possessions a team needs to win games.