Bill Russell, the greatest winner of all time, the impetus of a championship streak that will never be matched, and a champion of civil rights, has died. He was 88.

An announcement… pic.twitter.com/KMJ7pG4R5Z

— TheBillRussell (@RealBillRussell) July 31, 2022

Losing Russell is an immeasurable loss for the sport and humanity as a whole. No words can accurately capture the true impact he's had on everyone in every endeavor he undertook. Russell never truly lost, he only suffered minor setbacks on his way to greater victories.

William Fenton Russell was born in Lousiana and won two high school state championships before going to San Francisco to win two more NCAA championships. He followed that up with a gold medal in the 1956 Olympics.

Russell was the NBA’s first black superstar, not only winning five MVPs over his career, also finishing second twice, third twice, and fourth twice. He’s an 11-time All-NBA player and a 12-time All-Star over his 13-year career. He won 11 titles, suffering the indignity of failing to win it all only twice.

He averaged 15 points and 22.5 rebounds per game for his career, 16.2 points and 24.9 rebounds per game in the playoffs. He played in 10 Game 7’s and never lost a single one.

The NBA had been integrated in 1950, six years before Russell joined the league. Chuck Cooper was the first black player drafted by an NBA team, taken by the Celtics but gone before Russell got there. But the arrival of black players didn’t mean the floodgates opened for them.

Some of the best of the time played for the Harlem Globetrotters. In fact, it was the Globetrotters wins over the champion Minneapolis Lakers in a pair of exhibitions that helped pave the way for NBA integration.

If it wasn’t for a bad contract negotiation, Russell might have been on the Globetrotters too. But when that went south, Russell entered the 1956 NBA draft.

The Rochester Royals had the first pick in the draft (Tommy Heinsohn had already been taken by Boston with the territorial pick). They were struggling to turn a profit and the arena needed to be filled when basketball wasn’t being played. Red Auerbach and Walter Brown, the Celtics owner and one of the founders of the Ice Capades, knew this was the case and went to the Royals with a proposition.

You don’t draft Russell, and we’ll throw you the ice show for a bit to help pump a few bucks into your operation. They agreed, which was the first of many, many bad decisions for the franchise that ultimately became the Sacramento Kings.

The St. Louis Hawks had the second pick, but they moved it to Boston for St. Louis native and local hero Ed Macauley and Cliff Hagan. The Celtics took Russell, and beat St. Louis that season for his first championship. The Hawks beat the Celtics the next season, but never won again. Boston whipped off eight in a row behind Russell.

This is what he got future Hall of Famer Dolph Schayes to say after a single playoff game against him: “How much does that guy make a year? It would be to our advantage if we paid him off for five years to get away from us in the rest of this series.”

Minneapolis coach John Kundla said, in that same piece, “We don’t fear the Celtics without Bill Russell. Take him out and we can beat them … He’s the guy who whipped us psychologically. Russell has our club worrying every second. Every one of the five men is thinking Russell is covering him on every play. He blocks a shot, and before you know it, Boston is getting a basket, and a play by Russell has done it.”

The psychological warfare was Russell’s secret weapon, maybe because he was constantly engaged in it outside of basketball. The rampant racism of his time was constant at home and on the road. Throughout his life, he witnessed it over and over again, and when it robbed him of accolades he earned on the court, he steeled himself against the slight by doing something no bigot to take from him.

Win.

His ability to focus was arguably his greatest strength. Drowning out the outside noise gave him a singular focus on the court, and he used it to learn every player’s tendencies. He applied it by baiting players into thinking they could use a move against him and, when they went back to it for a second, third, or fourth time, he’d block the shot (or feed them what reporters used to call a Wilson burger) Once players were blocked, often seemingly out of nowhere, they’d nervously look for him the next time they felt like they were in a position to score.

Russell didn’t have the benefit of an on/off switch like someone like Kevin Garnett. Normal KG is amiable and willing to talk and have fun, but he whipped himself into heated frenzies on the court to get himself to his desired competitive level. Russell had to be on alert at all times.

He grew up in the segregated South, and experienced some of the worst a racist world had to offer. His ascension to NBA stardom did little to cut the edge off some of the overt racism.

Black players were refused service at a Lexington, Kentucky restaurant before an exhibition game.

“All of the black players were denied service—not just the black players for the Celtics,” former Celtics forward Satch Sanders said.

Once their hotel realized the men were members of the NBA, they changed their tune, but that was no consolation to them. They wanted to be treated as equals simply because they were equal, not because they could play basketball.

Hotel management told them they’d be denied service if they weren’t NBA players.

“Based on this criteria, Bill Russell quickly decided that he would not play in the game,” Sanders said. “The other black players on the Celtics—myself, Sam Jones, K. C. Jones—felt the same way about the situation. It was an easy decision to make.”

Russell and the black players left. The white players played.

Someone broke into his Boston home in 1963, vandalizing it with racist graffiti and defecating in his bed. Boston’s reputation in racial matters has never been great, and this was a time in history where that reputation was earned.

“He had issues with the Boston scene,” former Celtic and teammate Sanders told the Boston Globe. “And those had never, in his mind, been cleared up.”

“Boston itself was a flea market of racism,” Russell wrote in his memoir Second Wind. “It had all varieties, old and new, and in their most virulent form. The city had corrupt, city hall-crony racists, brick-throwing, send-’em-back-to-Africa racists, and in the university areas phony radical-chic racists... Other than that, I liked the city.’’

All the while, Russell channeled his rage towards two things: social justice, and winning basketball games. He wanted to use his fame and fortune to fight for things he stood for no matter how it impacted him personally. Whether it was standing by Muhammad Ali’s fight against the Vietnam War or attending the March on Washington, Russell was very visible with other star black athletes of his day.

By winning basketball games, Russell made sure no one, no matter how bigoted, could refute a black player’s greatness. Racist attitudes during the beginning of his career created a feeling that black players weren’t smart or coordinated enough to play a sophisticated sport like basketball; that they were not human enough to embrace its intricacies and were, instead, better suited for more primitive sports like running fast and jumping high.

Russell could do those things, too, but he used all the tools at his disposal to meet his goals. His mind games were bolstered by his elite athleticism. He was a world-class high-jumper, and he was ready to compete in that event in the Olympics. There was a plan to keep Russell off the Olympic basketball team because he’d signed a professional contract, but that ended up being resolved. He was a high-level sprinter as well, so when he took off down the floor, he could easily beat other players.

There are three moments in his life that, in combination, may best define Russell:

-The 1969 NBA Finals.

-His number retirement ceremony.

-The unveiling of his statue in Boston.

1969 was Russell’s final year in the NBA. It was his least productive, and it was becoming clear that Boston’s time as the league’s unbeatable juggernaut was coming to an end. The Los Angeles Lakers had home court advantage, which they used to take leads of 2-0 and 3-2. Home court was being held throughout the series, which led to a lot of Lakers confidence when they went home for a deciding Game 7.

Then-owner Jack Kent Cooke was ready to make a show of what he felt like would be an inevitable Lakers victory. He put out flyers around Forum which read:

"When, not if, the Lakers win the title, balloons [inscribed 'World Champion Lakers'] will be released from the rafters, the USC marching band will play 'Happy Days Are Here Again' and broadcaster Chick Hearn will interview [Lakers stars] Elgin Baylor, Jerry West and Wilt Chamberlain in that order."

Russell caught wind of the plan, and noticed the net full of balloons at the top of the arena.

“Those f---ing balloons are staying up there,” he said.

He wasn’t lying.

The Celtics held off the Lakers for a 108-106 win. Russell only scored 6 points, but he had a team best 6 assists (his passing was always an underrated aspect of his career) and 21 rebounds without coming out for a rest. You can blame that one on his coach, who was also Bill Russell. He had become the NBA's first Black head coach taking over for Auerbach in 1966.

His final three years in uniform were as player-coach. There were no assistant coaches, meaning Russell had to do all the thinking of substitutions and strategy on the fly as he was playing. On top of trying to defend, rebound, and pass, he had to keep track of who had how many fouls, who was playing poorly, who was getting tired, and when to call timeouts. The game wasn’t quite as complicated back then as it is now, but that’s still a heavy burden for one person to bear.

After the 1969 Finals, Russell quit the game, and he quit Boston. He went on to have a mediocre coaching career with Seattle and Sacramento. He did some TV work, too, and it was during his time at ABC that Auerbach and the Celtics planned to retire his number.

However, Russell wanted no part of it.

“Red knows how I feel about this,” Russell said “I’m not that type of guy.”

This was like two rams butting heads on a mountain top. Auerbach was raising his number 6 on March 12, 1972 whether Russell liked it or not. So they came to an agreement.

“The only way he was going to participate would be if it was before the game,” Heinsohn, then the team’s head coach said. “He respected his teammates... He considered the Celtics his family, so he wasn’t totally averse to them doing it. But he didn’t want it to happen in front of the fans.”

So, in a small, private ceremony before the game, and before fans were let in, Russell stood with some of his former teammates and watched his number go into the rafters.

It wasn’t until 1999, when Russell’s relationship with the city itself began to thaw, that he sat for a full, actual retirement ceremony.

It’s said that time heals all wounds, but it’s hard to say if it’s true here. It may have healed them enough for Russell to emerge from his relative solitude to become part of the NBA landscape again.

Boston’s evolution in terms of racism may have helped as well. The city still has many issues as do most cities in America, but the slow march towards equality has brought the city quite a distance from what Russell endured.

The momentum to honor Russell, one of the city’s truly great sports heroes, had reached a peak. A statue honoring him was finally going to be made. Many teams have honored their legends with statues outside of arenas, and Boston was on a path to do the same… until Russell refused.

He didn’t want some ode to his individual accomplishments. He gave his approval to the honor only after it was tied to a mentoring program created for city children. The statue was placed in Boston’s City Hall Plaza, symbolically near the worst images of Boston’s bussing crisis. The statue is surrounded by other statues of children, and bears the inscription “There are no other people's children in the United States. There are only next-generation Americans.”

These three things are Russell in a nutshell. Fiercely competitive to a point where failure simply isn’t an option; fiercely private and loyal to his teammates, for whom he’d given his body and soul on the court; fiercely fighting the injustice and inequality that envelop too many.

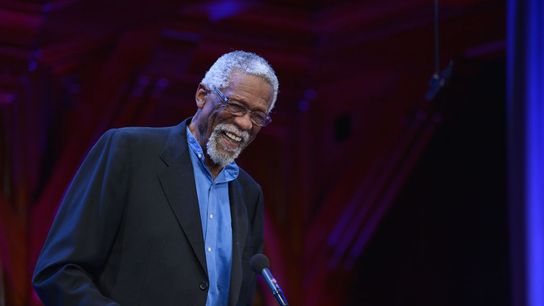

In 2017, Bill Russell stood on stage in New York City to accept a lifetime achievement award from the NBA. Joining him on the stage were some of basketball's greatest centers of all time.

Alonzo Mourning. Shaquille O’Neal. David Robinson. Dikembe Mutombo. Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

He stood there and took it all in. For a full five seconds he looked at this amazing array of big men through the years, standing there to honor him. It felt poignant. It felt emotional.

Russell then pointed to each of them, put his left hand up to his mouth, and said,

“I would kick your ass.”

The place exploded. Russell let out his usual shriek of a laugh. It was glorious.

Oh, and he was right. He would. He’d find a way. He always did.

Russell is not only a Celtics legend and he’s not only a Boston legend. He’s a sports legend and a human legend. He earned his Presidential Medal of Freedom many times over.

Losing Russell leave an unfillable hole in the game of basketball. He is the standard by which champions are measured, and none can hold a candle to his greatness.

NBA Commissioner Adam Silver issued the following statement today regarding the passing of Bill Russell: pic.twitter.com/DGX6ukOT4b

— NBA Communications (@NBAPR) July 31, 2022