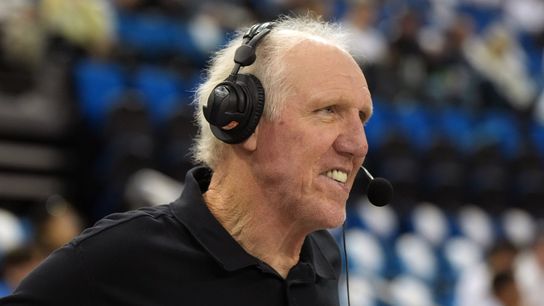

INDIANAPOLIS — Bill Walton, Hall of Famer and two-time champion, including the 1986 title with the Celtics, has died. Walton, 71, had been in a prolonged battle with cancer.

Walton will be remembered as not only one of the best big men to play the game but also as one of the NBA’s greatest personalities. He left everyone he met with a memory and a story.

The problem with a moment like this is where to start with the stories. Do you start from the beginning? Do you start at the end and work backward? Do you hopscotch around aimlessly like Walton would on so many college basketball broadcasts?

It was that stream-of-consciousness style of color commentary, replete with the imagery that only a flower child like Walton could muster, that grew his legend. His second act as a broadcaster is what drew so many to him because no one knew what he’d say or what natural phenomenon he’d reference. His commentary was perfect for the social media era because his tangents fit so perfectly into shareable sound bites.

It was the Tommy Heinsohn path, except Tommy was more steak, beer, and cigarettes while Walton was quinoa, ayahuasca, and kine bud. Walton was a legend who had already been a legend.

UCLA assistant coach Denny Crum scouted Walton and told head coach John Wooden that Walton was the best high school player he’d ever seen. Walton grew up idolizing UCLA and jumped at the chance to join Wooden’s juggernaut.

Together they’d win two national titles, whipping off an 88-game winning streak in the process. Walton won three national collegiate player of the year awards, two Final Four Most Outstanding Player awards, and three first-team All-American selections.

He was drafted by the Portland Trailblazers and found immediate success. He led the Blazers to their only championship in 1977, his third year in the league. He was the NBA’s leading rebounder and shot-blocker that season, and he won the league’s MVP the following season, despite only playing 58 games because of a broken foot. Walton returned for two playoff games before breaking his foot again.

He demanded a trade that offseason, a decision he later said he regretted. During a return visit to Portland in 2009, he called the decision “a stain and stigma on my soul. I can't wash it off. But I can come back here 35 years later and try to make a difference. Try to make it better. Try to light the candle.”

His move to his hometown San Diego Clippers was a disaster. He played just 14 games in his first four years with the Clippers due to injury, but after numerous surgeries to rebuild his foot, he started to rebuild his career.

Which brought him to Boston.

He arrived as part of the Cedric Maxwell trade, which actually cost him a bit of money. In a podcast appearance, Walton told Adrian Wojnarowski he gave back all the deferred compensation the Clippers owed him just to get away from Donald Sterling. After the trade was done, he came to Boston but hit a big snag: his physical.

“I could hear the doctors talking among themselves: ‘What are we going to tell Red (Auerbach)? We can’t pass this guy. Look at his feet. Look at his knees. Look at his hands and wrists. Look at his spine. Look at his face. There’s no way we can pass this guy,” Walton said.

“And then Red, he bursts in through the double doors at Mass. General Hospital … and Red says, ‘Shut up. I’m in charge here.’ And Red pushes his way through all the doctors, comes over. I’m lying on the table there in the doctor's examining room. Red looks down at me. He says, ‘Walton, can you play?’ And I looked up at him with the sad, soft eyes of a young man who just wanted one more chance. One more chance to be part of something special, to be part of the team, to be with the guys one more time. And I looked up at him, and I said, ‘Red, I think I can. I think I can, Red.’

“And Red took a step back, folded his arms, and took a drag on that cigar. Oh my gosh. And he held that smoke in as long as he possibly could, and you could just see all the machinations going on, all the calculations, all the deliberations as to how this is all going to play out. Finally, he just exhaled, and I swear that smoke came out green, Adrian. And it was shamrocks and leprechauns up against the white LED lights on the wall. And Red, through the smoke, with a big, cherubic grin on his face, looked at the doctors, looked at me, and he said, ‘He’s fine. He passes. Let’s go.’”

Walton played a career-high 80 games for Boston that season, winning Sixth Man of the Year. The visions of him catching the ball in the post and feeding a cutting Larry Bird for a layup still dance in the heads of those of us old enough to remember. The Celtics won the championship that year, giving Walton his second championship in what would be his final full season in the NBA.

“If Bill could have finished his career from start to finish healthy, there's no telling where he’d be ranked in the best players ever,” Bird said of Walton. “He’s that good. He had all the skills.”

Walton sacrificed his body for his career. This obituary would have been written 15 years ago had it not been for one more surgery to ease the debilitating pain that had grown over the years. Walton was physically and mentally broken and contemplated suicide as a way to end the pain.

“My joyous life was quickly reduced to nothing … I couldn’t sit, stand or lie down. I couldn’t work, speak, think, leave the house or care for myself. I couldn’t even get up off the floor. I had to eat my meals lying on the floor, face down. And it was getting worse,” He said. “Although I had a great family and wonderful friends, my life was so limited, so painful, so empty, I was ready to end it … I found myself searching for bridges. I was looking for the highest ones, with the longest of falls and the hardest of bottoms.”

The surgery in 2008 was a game-changer for Walton. Eight months after the procedure, he realized the pain had subsided, and he began a new chapter that brought him back into the public eye.

“I have two fused ankles, knees, hands and wrists that don't work. At least 11 bolts in my body,” he said. “I went from thinking I was going to die, to wanting to die, to being afraid that I was going to live, to now seeing rainbows, calliopes, clowns, and dreams of a better tomorrow.”

Walton’s zest for life returned, and he returned to the broadcast booth, unleashing a legendary run of on-air shenanigans that will never be duplicated, mostly because they came from such a genuine and earnest place. No one can do what Walton did on television because it was so uniquely him.

The basketball world is filled with Bill Walton stories today. Everyone who met him has one. The greatest shame is that now there are no new ones to tell. Luckily for us, Walton’s legend was so great that the old ones will carry us for a long, long time.