There’s not a whole lot that rattles Jeremy Swayman.

Operating with such serenity amid both the chaos around him and the cacophony of cheers and jeers raining down from above shouldn’t necessarily come as much of a surprise.

Frankly, it kind of comes with a gig in which your regular duties involve stopping screaming salvos of vulcanized rubber, night in and night out. But even with said job description, it hasn’t taken very long for the affable young netminder to endear himself in the Bruins’ locker room due to his mental fortitude under pressure.

"I have a lot to learn from that kid,” Brandon Carlo said of Swayman. “Mentally, he's amazing. He seems to be unfazed by a lot of things. … His ceiling is immense. And it's pretty special. Not a lot of people have that.”

Granted, not a whole lot of people have found themselves in Swayman’s shoes during high-leverage situations.

Sure, it’s one thing to square yourself up for an impending howitzer from Alex Ovechkin on the power play. In the NHL goaltending fraternity, that’s simply an occupational hazard.

But when you’ve had a run-in with a grizzly bear just south of the Yukon, an Ovi clapper isn’t really going to be elevating your heart rate.

“We had a big brownie come through our campsite at like 4:00 a.m. one time, sniffing our tent,” Swayman recalled from his days hiking the 33-mile Chilkoot Trail through the Coast Mountains. “We had to get pretty loud, just to let him know that we were there.”

These days, Swayman might feel at home in the crease at TD Garden — but his true home lies 4,500 miles west of Boston, up in Alaska.

And even though the Blue Hills within the Commonwealth don’t quite measure up to the Chugach Mountains that paint the canvas beyond the Swayman family abode up in Anchorage, Swayman doesn’t need to search very far for a vestige from America’s last frontier.

After all, the backplate of his latest goalie mask is embossed with an outline of the 49th State.

Getty Images

“Alaska is a pretty unique place to come from,” Swayman acknowledged. “And it's a big reason why I'm where I'm at now. The people that have supported me, and helped me to get to where I wanted to be is tremendous. When I get to look at the back of my helmet before every period, that just reminds me and gives me an extra motivation to do my best and make them proud.”

For Jeremy’s father, Ken, his son’s affinity for his home state comes as no surprise.

Countless hours spent working on his craft in rinks across the state might have set Swayman on his path toward the NHL. But between father and son, the fondest memories up north often revolved around the many treks up into the Alaskan wilderness — and that shared love for the great outdoors.

“You can take the kid out of Alaska. But you can never take Alaska out of a kid,” Ken Swayman said to BostonSportsJournal.com. “That's in his blood.”

———

Before Swayman could even walk, both he and his father were joined at the hip — be it at the University of Alaska-Anchorage hockey team’s barn or the many trails just outside of Anchorage.

During hockey games, Ken Swayman and his son were often a fixture behind the Seawolves’ net, with the elder Swayman serving as a volunteer doctor for the team. Just a few months old at the time, Jeremy would take in the sights and sounds of the game while tucked away in his father’s backpack, watching intently as the biscuit skittered up and down the frozen sheet.

That same Kelty backpack from REI would come in handy when Ken Swayman would opt for jaunts out into the nearby Chugach National Forest, the nearly seven-million-acre preserve that dwarfs the entire state of Massachusetts in total area.

For Ken, a podiatrist who originally hails from Brooklyn, that love of the outdoors didn’t manifest until he was around 10 years old — when he first climbed Mount Washington with his cousin.

He was instantly hooked, expanding his horizons to the Catskills and the Adirondacks before eventually moving out west for medical school and a residency, where destinations such as Yosemite, Mount Rainier and the North Cascades beckoned.

When an opportunity presented itself up in Alaska, Ken couldn’t say no. Fast-forward a few years later, and Jeremy was fastened to his backpack, with Ken ingratiating him to all that Alaska had to offer: the expanse, the wildlife and the escape that a trek through the woods could provide.

“It just became part of Jeremy's life as a spin-off of it being so relevant and special in my life,” Ken noted. “And he just bought into it - hook, line and sinker.”

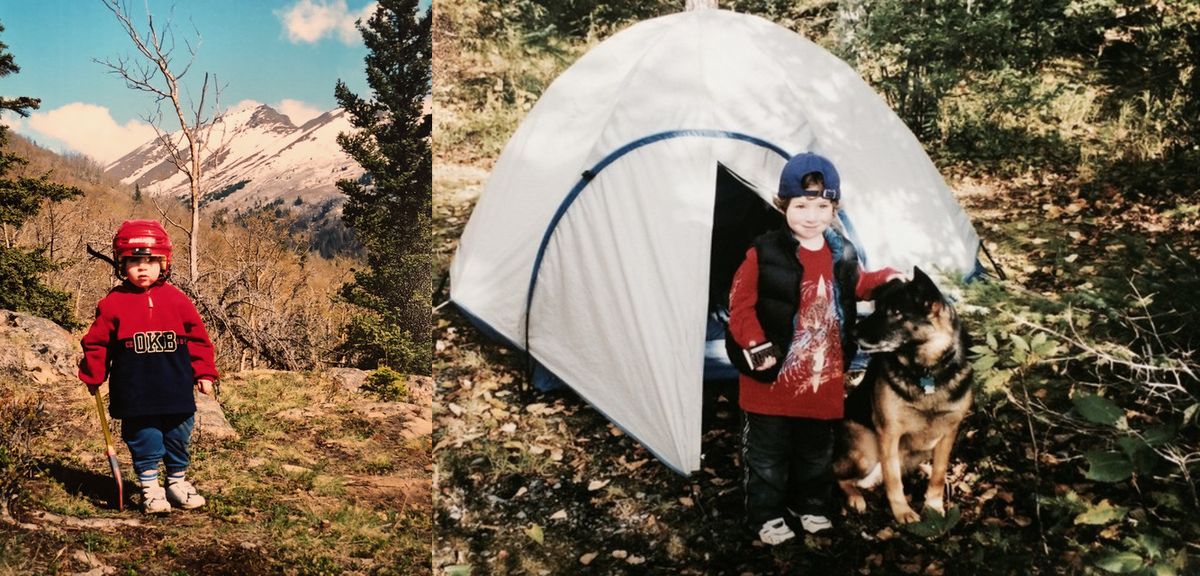

It didn’t take long for Jeremy’s two worlds to begin to meld. Still just a toddler, Jeremy began to don a bright red Bauer bucket during his appearances at the rink. Eventually, the helmet became a necessary accessory whenever Jeremy hit the trails with his father.

“He barely just started to walk,” Ken recalled. “And the funniest thing is whenever we'd go on hikes, he put the helmet on. … It's hysterical. He'd even sleep with it and I got him gloves. He'd want to bring the gloves too.”

PHOTOS COURTESY OF KEN SWAYMAN

If the Swaymans were hitting the trails, Jeremy's red Bauer helmet (pictured, left) wasn't far behind.

As Jeremy grew older, the trails became steeper. The hikes far more daunting.

As if that was going to deter a youngster who, at one point, was competing against second graders as a pre-K participant on a mite team.

“The more I threw at him, the more he would do,” Ken said.

———

By the time Jeremy was 10, the Swaymans were reeling off extended backpacking journeys, some spanning 50 or more miles.

While Swayman’s teen years were eventually inundated with hockey camps during the summer, both father and son made the most of a lighter docket whenever it became available to them, with the two making an annual trip up to the vast Denali National Park for close to a decade.

With North America’s tallest mountain serving as an omnipresent backdrop, Jeremy and Ken would often hop aboard the national park’s bus service (the lone form of transportation into the park), and get out at various points along the 80-mile road.

“There are no trails in the park,” Ken said. “ I got some guidebooks and talking to people over the years. 'Well, you get off at mile 32 and hike north through this valley. Climb over this ridge. You got to forge this river and then come back and you'll end up at mile 41.' So it's like a 12-mile loop hike and then the bus picks you up, heading back out to the visitor center. And Jeremy and I would do stuff like that.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEN SWAYMAN

In a cerebral scrapbook full of memories, those two-week stints up in Denali routinely come to mind for Ken.

The encounters with bears, wolves, coyotes and wolverines. Close friends and family joining the camping expeditions. Roaring campfires illuminating a star-speckled sky.

At one point, they even took part in a several-day course that studied wolves within the park.

“You're out there and you're tracking wolves with electronics," Ken said. "And I got pictures of Jeremy - he's a little kid, he could barely hold this shit. He's got this backpack on with this huge antenna. And we're out there tracking wolf packs. So I tried to expose him to all that stuff in the summers and he just bit in.

“He just was all over it. Those discovery hikes, it'd be like 8-10 people, and you'd see the volunteer ranger, they'd be hiking up ahead. And guess who was right next to them? Jeremy. He was right up there …He was just a rock star. And now he knows a lot. So when he goes on a hike, he knows what to do."

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEN SWAYMAN

———

That love for all that nature has to offer hasn’t waned for Jeremy over the years, even as hockey has obviously risen to the forefront.

When the time came for Swayman to start fielding offers from colleges, what stood out about Red Gendron and the University of Maine’s initial pitch had little to do with Alfond Arena and his potential role as the Hockey East program’s No. 1 netminder.

“I don't think they talked too much, honestly, about hockey,” Alfie Michaud, Swayman's goaltending coach at Maine, recalled. “It was more about what Maine has to offer. … I know Red did his homework.”

“I remember Red talking about the Penobscot River and just about how there's plenty of hiking trails and fishing opportunities,” Swayman added. “He got a tip - he knew that I was pretty outdoorsy. Red, he's a thesaurus, a dictionary, and an atlas, all in one. So he knew everything about nature and history. He knew all the areas to talk about up in Maine and I was sold."

Given what Swayman’s current job entails — and the pressure that is often funneled toward the man serving as the last line of defense on an NHL roster — finding a proper release from the weight resting on one’s shoulders is a necessity.

Of course, Swayman may not be sneaking in a quick summit of Mount Monadnock ahead of his first career playoff start on Friday night.

But be it at the summit of one of the many Pacific Coast peaks, along the banks of the Kenai River or in net ahead of a pivotal Game 3 showdown against Carolina, Swayman has had a knack for staying in the moment.

“Just enjoy the journey,” Michaud said. “Stuff always takes care of itself. I feel the good guys are just so good at being in the moment and they can lock in. Our thing was being where your feet are at. Not just with him, but I think with everybody. Just be where your feet are at. Be the best you can in that moment. And if you can manage to stay there instead of drifting and thinking about the future or worried about the past that you have no control over, you're probably better for it.”

PHOTO COURTESY OF KEN SWAYMAN

———

Jeremy’s schedule is a bit tougher to map out these days. Ideally, his itinerary will be crammed through the end of June, Ken hopes.

But when the offseason does finally arrive, another hiking trip is probably close behind.

“It's just disconnecting,” Jeremy said of the appeal of getting outside. “I think that you get a really good appreciation for things when you don't have cell service, you don't have newsletters, you don't have anything going on — any contact with people. That's when you really appreciate the little things.

“You realize that the little things aren't so little. They're actually big things. The necessities of the little things like water, food, good hygiene, good health. When you're backpacking and you're in the 48th mile of a 60-miler or a 70-miler, you're really appreciative of doing this. Because I'm so fortunate to have the opportunity and you get to see some pretty incredible things that not everyone gets to see.”

There are still plenty of expeditions that the Swaymans have yet to chart together. While Jeremy will still set aside time to go up to Alaska for a few weeks each summer, Ken’s recent move down to northern Arizona should open the door for outings to the Grand Canyon, float trips down the Colorado River, and a tour through Utah’s Mighty 5 national parks.

Before COVID struck, they had planned a three-week journey to the Mount Everest South Base Camp, tucked away amid the sky-shearing pillars of the Himalayas. One bucket-list item for Jeremy involves the Pacific Crest Trail — a 2,600-mile journey from the Cascade Mountains of Washington all the way down to the arid Laguna ranges down in San Diego County.

Jeremy added a qualifier to such a journey, noting that he’d only join for about 200 miles of the trek. But the full 2,600 miles for his dad? He wouldn’t put it past him.

“He's one of the sole reasons why I've made it to this level and why I know what I know," Swayman said of his father. "The experiences I've had and the work ethic and the integrity — I've learned from him. There's not a better role model I could have asked for.”

For Ken, things have just about come full circle.

When they're back home, the Swaymans are still climbing — at times, the same trails that Ken first brought Jeremy on when he was strapped to his back.

But these days, Ken is more than happy to defer to his son and let him chart his own path.

Even greater heights await.

But nothing’s fazed Jeremy yet.

"When he was little, we would go hiking and of course, he was in a pack," Ken said. "When he was older, he was on my backpack. And then when he could walk and sustain some mileage, he could walk it. And I would always be pushing him to 'Keep going, come on. It's only eight miles and we'll be there.'

“And then there was this light bulb and this turn of events when all of a sudden — he's now in the front. He's where he should be. He's turning around saying 'Come on, dad. Get up this hill.' And that was a beautiful moment for me. The baton has been passed and now he's the leader and he became the leader. He's leading this hike. He's keeping the pace. He's like, ‘Go, Go, Go’ And that was, as a parent — that was a pretty special moment.”