Jerry Remy was always in a hurry.

As a player, Remy stole 208 bases across a major-league career that lasted 10 seasons. Not blessed with a big, strong body, Remy used his legs to run and to push drag bunts up the line. He did what he had to do, but he wasn't going to be outworked or outraced.

It was the same when he became a broadcaster.

Remy had to be first to the ballpark every single day. His one-time partner, Don Orsillo, once noted that this obsession intensified with the passing of time. Early in their time together, Remy would tell Orsillo to meet him in the hotel lobby at 3:15. That would give them 15 minutes to get to the ballpark and be there when the clubhouse opened at 3:30, the customary three and a half hours before first pitch.

The next year, the prescribed meeting time became 3 p.m. The following year, it was 2:45. And so it went -- every season, Remy's departure time got earlier by 15 minutes. In a world where people naturally slow down as they age, Remy fought that notion. Maybe his thinking went like this: If I'm slowing down, I better give myself more time to get where I'm going.

On rare off-days in the schedule, Remy took the same approach when going out to dinner. Once, he proposed a dinner time that was too early for Orsillo's taste, and decided to go by himself. A lover of good steaks, Remy arrived at a famed Chicago steak house and peered inside the window of the restaurant, like a child waiting for Christmas morning. Eventually, some worker inside took pity on him and unlocked the door, inviting him in even before the restaurant was officially open for business.

That was on the road. At home, because of his stature, the 3:30 rules didn't apply to him. When the clubhouse doors opened, Remy was already seated in front of a table, looking over game notes and statistics -- as though he had slept there. If he could, he probably would have.

Nobody was going to outwork Jerry Remy, who passed away Saturday night from yet another battle with cancer at 68. That was his attitude as a player -- when he was an undersized kid from New England, taken in the eighth round from a suburb of Fall River. New England high school kids had notoriously short seasons because of the weather, putting Remy at a distinct competitive disadvantage when it came to competing against players from California, Texas and Florida.

But Remy had the last laugh. Decades after his career ended, he delighted in recounting how he had beaten some of the "bonus babies'' who had been drafted earlier and paid far more. Without identifying or publicly embarrassing them, he would take pleasure in recalling how he had long outlasted players who arrived for their first spring training driving extravagant sports cars, paid for by their big signing bonuses. They may have been more skilled and more experienced, but they couldn't begin to match Remy's determination and desire.

He took that same work ethic to the broadcast booth. Recognizing that he had no particular professional broadcast training or background to serve as a color analyst, Remy was committed to learning on the fly. In later years, he would look back on his first few years in the booth with some embarrassment and, typically, an absolute absence of self-regard.

"I had no idea what I was doing,'' said Remy, unashamed to admit how much he had struggled.

Left unsaid was that Remy could laugh at himself because he had worked tirelessly to get better. He would cringe-watch old videotapes of his broadcasts, but there was an unspoken pride that he did everything he could to get better until he had become an exemplary analyst.

The word "icon'' gets thrown around far too frequently in sports, but that's exactly what Remy had become in the early 2000s. He was every bit as popular then as David Ortiz, Pedro Martinez or Manny Ramirez. He became an invited guest into the homes of millions of New Englanders, fans who lived and died with their favorite team. That was because Remy was one of them.

Even though he had played major-league baseball for a decade, the last seven with the team that he grew up watching, Remy carried a distinct everyman vibe. He wasn't necessarily as polished as some others. But he sounded like us -- dropping r's habitually, while adding them where they weren't needed. (I know one of my disappointments was that Remy, after being stricken midseason, never got a chance to tell viewers about "Kyle Schwahhhbahhh,'' because that would have been a real treat. I suspect that Remy would have immediately fallen in love with Schwarber, too, and not just because of his last name, but because he would have identified him as a player who loved the game, and as he famously demonstrated in the Division Series against Tampa Bay, as someone who was unafraid to laugh at himself.)

He could be famously stubborn. Some of the changes to the modern game drove him to the edge of frustration. But that stubbornness was evident away from the ballpark, too. Once, while driving to a spring-training game in Florida with Orsillo, he refused to fasten his seatbelt, choosing instead to listen to the car's incessant warning chimes for a 75-minute drive from Fort Myers to Bradenton.

Always, he was a reservoir of baseball knowledge. If a rundown was poorly executed, or a cutoff throw was bungled, I knew I could turn to Remy after the game or prior to the next one and have it perfectly explained to me.

It's well known that Remy was never truly comfortable with his celebrity, but on the occasions that a friend visited me in the press box, I knew that I could arrange for a quick visit to the NESN booth for a handshake, a smile and a quick picture. It was always a thrill to stop outside his broadcast booth, ask a visitor "Want to say hello to Jerry Remy?'' and watch their face light up at the prospect.

Shortly before Remy took ill this past summer, a friend in the media asked if I could help arrange for Remy to appear via Zoom for a podcast that was being recorded about the 1978 Red Sox season. Remy gave my friend a half-hour of his time, recounting that famed (and painful) season with incredible detail and insight. I was not surprised.

Occasionally, during his last absence, I would text him and offer encouragement for his battle. Sometimes, he would respond almost immediately. "Thanks, Sean. Been a tough go, but plugging away.''

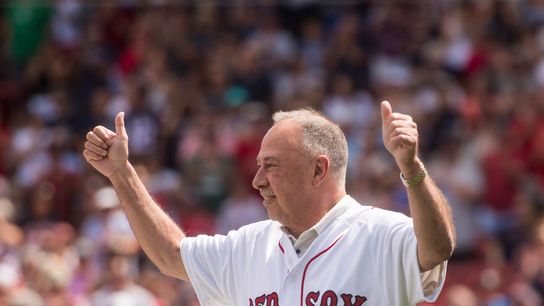

The last message I sent came the night he threw out the first pitch prior to the Sox' wild card game with the Yankees.

It read: "What a thrill to see you tonight, Rem. Hope you felt all that love. Stay strong.''

He never did respond to that one, which I completely understood. No doubt his phone contained hundreds of such messages that night.

But I was heartened by the reception he received that night. Unsteady and aided by a breathing tube, he managed to toss the ball to Dennis Eckersley, one of his broadcast partners.

Then, he was off, transported by the bullpen cart, circling the ballpark one final time — once again in a hurry.