It’s been nearly 25 years since Rick Pitino took control of the Boston Celtics, kicking off an era of dramatic disappointment that set back the franchise through the tail end of the 1990s and beyond. Most Boston fans would probably like to block out most of this era (beyond the drafting of Paul Pierce) but given the dearth of sports news during this quarantine, I decided this would be a good time for a fuller look at Pitino’s body of work.

Growing up as a teenager in Pitino’s reign, there was always the understanding from afar that he wasn’t making the right moves and his players weren’t responding to the hard practices and relentless full-court pressure strategy over his four years at the helm. However, after going down a research rabbit hole with his specific moves and their sequencing, it feels like some of these decisions need to be put in perspective over two decades later, along with the underlying impact on the franchise. With that in mind, let’s dive headfirst into getting a closer look at some of the biggest missteps of the Pitino era, which practically started from day one.

Setup:

Year 1 of the Rick Pitino Era

Summer 1997

Overview: The former Kentucky head coach took control of the Celtics just ahead of the NBA Draft Lottery in 1996. While the narrative was always about missing out on Tim Duncan for Pitino, the fact was despite having two picks in the lottery, the C’s only had a 36 percent chance at landing the No. 1 pick. They held steady with the Mavericks pick at No. 6 (sixth-worst record) and dropped from the best odds at No. 1 to the No. 3 pick in the draft when the Spurs (Tim Duncan) and Sixers (Keith Van Horn) leapfrogged them.

That left the Celtics with two top-six picks in what ended up being one of the weakest draft classes in NBA history after Duncan went at No. 1 with just three All-Stars among the 57 picks. Pitino seemingly drafted his backcourt of the future with Chauncey Billups at No. 3 and Ron Mercer at No. 6, leading into a pivotal summer for Pitino, who was looking to revamp a 15-win roster.

A Disasterous Free Agency

NBA salary cap rules have evolved plenty over the years but the main principals were still in place in the summer of 1997 when Pitino took control along with general manager Chris Wallace. The Celtics had the ability to create significant salary cap room but in order to do so, they would need to renounce the ‘Bird Rights’ on several of their own free agents. Normally, teams do not overhaul their own roster and renounce players in order to up significant cap room unless it's for a significant upgrade. The Celtics didn’t do it for nearly 15 years during Danny Ainge’s tenure as president until the summer of 2016 when Al Horford was signed for a max contract.

All-Star names weren’t available on the free-agent market in the summer of 1997. In fact, it was a very quiet summer when it came to big names. Power forward Brian Grant (Blazer) signed the biggest deal of the summer as a parade of solid starters/role players (Bobby Phills to Charlotte, Clifford Robinson to Phoenix, and Bison Dele to Detroit) switched squads with the big fish staying put.

For a 15-win squad, normally this would be the type of offseason when you want to punt on dumping your own talent to clear cap room. None of those names listed above are worth reconfiguring your entire roster or future plans. Yet, as Pitino sought to make a splash immediately, he decided he wanted to clear the deck of arguably the best young talent on Boston’s roster.

Eight Celtic players were released or renounced in the first month of free agency by Pitino.

Some of these names were guys that he shouldn’t have had an interest in keeping around (Brett Szabo, Steve Hamer, Nate Driggers, Marty Conlon) but there were a few key pieces also cast to the side as well.

David Wesley (16.8 ppg/7.3 apg) was a 26-year-old that was allowed to walk and sign with the Hornets on July 1st for reasonable money ($2 million/year). The same went for 27-year-old Rick Fox (15.4 ppg), who eventually signed a cheap deal with the Lakers in August after weighing plenty of suitors who offered up to $5 million per year.

Electing to let Wesley and Fox go without compensation opened the door for Pitino to make his first big underwhelming move: Signing center Travis Knight.

The UConn product wasn’t exactly a prized piece out of college. After falling to No. 29 in the 1996 NBA Draft, the Bulls selected him but elected to pass on giving him the required three-year contract for first-rounders. They released him a month later and he was scooped up by the Lakers. The seven-footer made the All-Rookie second team with modest averages of 4.8 points and 4.5 rebounds in 16.3 minutes per game while backing up Shaquille O’Neal.

The Lakers were limited in what they could offer Knight in his next deal due to salary cap limitations and Pitino sought to pounce, offering up a seven-year, $22 million deal to lockdown the reserve center with a salary that was higher than the C’s No. 6 overall pick in Mercer in 1997.

''I really have mixed emotions,'' said the 22-year-old Knight to reporters at the time. ''I should be elated right now, but I'm not. I feel so much loyalty (to the Lakers.) But you work at something as hard as you can, and then it's there. The security. That's the rest of my life, right there.''

Two of Boston’s top three scorers were out the door and the big splash to replace them was a second-year center that had averaged over four points per game. Knight ended up averaging 3.4 ppg during his seven-year NBA career.

Pitino wasn’t done handing out bad deals that summer though. He turned next to overpaying another reserve big in Andrew DeClercq, by quadrupling his salary to $1.2 million from his first two seasons with the Warriors after watching him post 5.3 points and 4.2 rebounds per game in the Bay Area. Another veteran big Tony Massenburg was brought aboard from the Nets as well. Pitino’s best work that offseason was identifying Bruce Bowen as a promising young piece after seeing him bounce around the minor leagues for the last few years. Of course, Bowen was signed to a low money deal and was let go years before he blossomed into a championship role player and All-NBA defender with the Spurs.

Pitino still clearly had a big scoring hole to fill with Fox and Wesley out the door though despite those big man additions. He also needed more salary cap room after a trade involving sending another top scorer Dino Radja to the Sixers for Clarence Weatherspoon and Michael Cage fell through. Radja instead was waived, with the C’s being forced to eat half of his $5.4-million contract on the cap.

The next target for Pitino was another former Wildcat in swingman Chris Mills, who had been a solid role player with the Cavs during his first four seasons. Bringing aboard the 28-year-old Mills didn’t make a ton of sense from a timeline perspective, especially after the younger Wesley and Fox were already let go to clear cap room but that didn’t stop Pitino from trying to make a splash. Eventually, he outbid Mills’ suitors in August to sign him to a seven-year, $34 million contract, a hefty price for a guy who only averaged 13.4 ppg on an average Cavs team in 1996-97.

Now, it would be one thing if Pitino didn’t have to give up anything to land Mills. However, a little more cap room needed to be cleared in order to make the contract work after the signings of Knight, DeClercq and company.

Pitino’s solution? Trade 24-year-old Eric Williams who averaged 15.0 ppg in 96-97 and was taken at No. 14 overall by the Celtics just two years ago for two second-round picks. Williams was only making $1.1 million in his third NBA season, while putting up the same type of production as Mills (and serving as a better defender in the process). The logic of giving up Williams for pennies on the dollar while bringing aboard an equivalent older replacement at big money was perplexing to say the least. It also could have been avoided with adequate salary cap management as well if the C’s had prioritized signing Mills ahead of the likes of DeClercq or Massenberg.

Alas, the deal was done. Mills signed one of the biggest contracts of the offseason and there was enough left over for the C’s to sign another backup point guard in Tyus Edney who had an underwhelming first two seasons in Sacramento. A look at the names that Pitino brought in that summer were essentially just players based on two categories: 1) Kentucky ties to Pitino (Mercer, Mills) or 2) players on elite college teams during Pitino's time at Kentucky that hadn’t amounted to much in the pros (Knight, Edney, DeClercq).

A look at Pitino’s first depth chart heading into that 96-97 preseason after the dust settled:

PG: Chauncey Billups, Dana Barros, Tyus Edney

SG: Ron Mercer, Dee Brown,

SF: Chris Mills, Greg Minor, Bruce Bowen

PF: Antoine Walker, Tony Massenberg

C: Travis Knight, Andrew DeClercq, Pervis Ellison

Summary

Pitino dumped four of Boston’s five top scorers and managed to tie up all the team’s salary cap space for the foreseeable future in order to land Mills, Knight, DeClercq and a couple of second-round picks. Incredibly, this offseason probably is not the strongest candidate for the worst decision of the Pitino era.

Up Next

An in-depth look at the 1996-97 campaign (aka the most successful Celtics season for Pitino in Boston) during which a top free agent was traded away during the preseason and a promising lottery pick was let go after just 50 games.

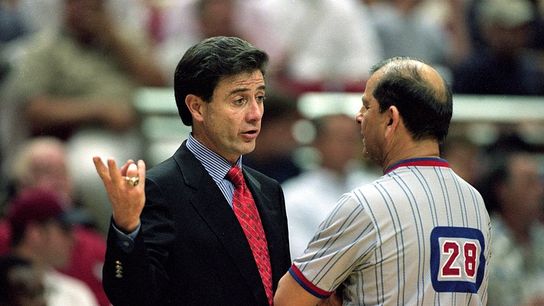

(Andy Lyons/Getty Images)

Celtics

Inside Rick Pitino's disastrous first offseason with the Celtics

Loading...

Loading...