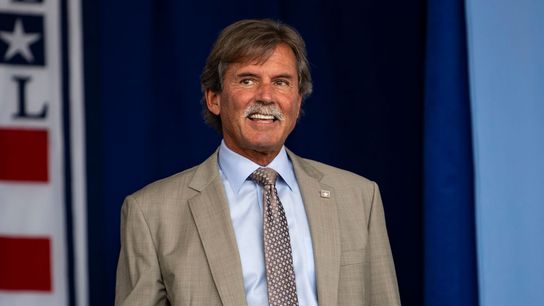

The best athletes have an innate sense of timing. The best broadcasters, too.

That's why, after 24 years as a pitcher and another 20 in the broadcast booth, Dennis Eckersley noted Thursday: "It's time for the hook.''

The quote, uttered during Thursday's telecast on NESN, was typical Eckersley: irreverent, self-effacing, candid, and funny as hell.

Eckersley revealed his decision to retire from broadcasting in early August. The news came 10 months after the death of close friend and former on-air partner Jerry Remy, and served as a cruel blow to Red Sox fans who had enjoyed both.

Eckersley had been debating when to retire for the last "couple of years.'' He admits that Remy's passing was a factor in his decision ("It all adds up''), along with a debt he feels to his family -- his wife Jennifer, his adult children and his twin grandchildren in California. For so long, he's devoted time to the game. Now, he figures he owes some of that time to them.

Throughout September, Eckersley arrived at Fenway with a mental countdown in his head, savoring the number of games left.

"I tried consciously to do it,'' he said. "But you can't until it really gets closer. I've been trying to enjoy it, if there's such a thing. It's hard. I'm kind of afraid of it, a little bit, because of the finality of it. This doesn't happen in your lifetime; this is life. But I like the fact that it's my choice. So that's not a bad thing.''

Indeed, the Red Sox and NESN would love for Eckersley to remain in the booth for years to come. But once Eckersley made up his mind and informed them of his decision to leave, they respected it. They offered to have Eckersley work as few or as many games as he wishes going forward, with the option to greatly scale back his schedule while still being involved.

But Eckersley declined.

"This job, you've got to be all in,'' he said. "I'm not going to do 30-40 games. I can't do that.''

He freely admits the changes that have taken place to the game in recent years have made the job less enjoyable. The games are longer, and yet, somehow feature less action than ever before. There's a monotony to the "three true outcomes'' approach by hitters.

"It's not a factor (in my decision), but it's real,'' he said. "And now that I'm getting out, they're changing the goddamn rules. It's there, but it goes along with the job. You go along with it. If you bitch and moan, what good does that do?''

What concerns him more in retirement is how he'll replace the passion he has for the game. Unlike some players-turned-broadcasters who mostly follow only the team for whom they work, Eckersley is a baseball junkie. He returns home from Fenway, and watches late games from the West Coast. He acknowledges that baseball is the first thing on his mind when he wakes up in the morning.

"That's a tough one,'' said Eckersley. "(The game) gets your blood going. It really does. There's nothing like it. I wish I had a hobby.''

He occasionally plays golf, though a balky right shoulder from his playing days limits him on the course. "So I'll play (lousy) golf until I figure out how to fix my shoulder. But that's fine. Golf you can only play so much. Unless you're really good, that would be great. I'd give anything to be really good, like Wake (Tim Wakefield). But it ain't going to happen.

"But I'm just going to try to get out of thinking about 'Denny Boy' all the time. You know what I mean? Because we're consumed with this. I'm not a full person. I haven't been a full person in 50 (expletive) years. It's always about 'Gotta get ready for the season.' And then, (broadcasting). My mind's always somewhere else. I know in the offseason, I become a person sometimes. That's a good feeling. I want to keep that feeling year-round. I don't know how that's going to go.

"I hope that I can open up, be more curious about life, and all that (stuff). Traveling is the worse; I'm sick of traveling. But my wife wants to travel. I don't know. The biggest thing is looking forward to not having that grind anymore, always thinking about baseball. You can't get away from it.''

Still, he's not about to quit baseball.

"I'll be watching,'' he said. "I'll watch the A's. Obviously, you watch any team you want now. I'll be drawn (to the Red Sox), to see how this pans out. How can you not, because of where we are right now? It's going to get better, I would assume. So I'll be curious to see what happens here. But I will follow it. It's in my blood. I can't get enough.''

For 20 years, Eckersley relentlessly did his homework, petrified that a situation would arise or a player would come and he would be uninformed and embarrass himself on the air.

Without that outlet, that competitive zeal to be as good as he can be, he worries.

"Where am I going to go? Where am I going to find passion?'' he said. "First of all, I'm going to come out of myself, and I'm hoping that's a better self. To be there for somebody else. For once in my (expletive) life, it's not going to be about me all the time. I owe that to some people.''

As much as Eckersley looks forward to a more relaxed lifestyle, without daily commitments, the uncertainty of the future produces some anxiety.

"I'm afraid. I'm always afraid. I wish I wasn't,'' he said. "Of life in general. What's next? I live on that edge, I guess. I'm just used to being on the edge. When I look at it like I'm not on the edge anymore, it seems great. I can't wait. But do I need that edge? I don't know. It's all from me -- insecurities, vulnerabilities, all that goes through everybody. Some people are worse than others, but everybody's got some of it.''

Eckersley's association with NESN began 20 years ago, and for a while, consisted solely of studio work on the pre- and post-game shows. Before long, he was working for TBS, and could have remained there, but opted out.

"I wasn't into it,'' he said flatly. "I felt naked. I never felt real secure doing national stuff (because he wasn't around the teams all the time). I hate that. I didn't like it. I'm sure a lot of guys would have kept doing it, but I've been very sensitive in recent years toward my mental health and not doing what I didn't like to do. I always keep that in mind.''

As he thinks about Life After Baseball next March and April, he relishes the freedom that promises.

"It will probably be heavenly,'' he said. "No spring training, no grind. I'll be somewhere the weather's good, I'll tell you that.''

He worries somewhat about his financial security.

"I'm not holding big iron here,'' he said. "But if I had made $50 million or whatever, like (players) make nowadays, would I have (worked as a broadcaster?). Maybe not. I think a lot of guys nowadays wouldn't want this job. I was meant to do this. I was meant to come back to Boston.''

Eckersley played for five different franchises in his playing career -- Cleveland, Chicago, Oakland, St. Louis, and of course, Boston. He broke in with Cleveland, became a Hall of Famer in Oakland and spent two seasons in St. Louis. But Boston always felt like his baseball home.

"I'm a Red Sox,'' he said. "That's the way I've been treated, too, beyond this booth. The way I've been treated and the respect I feel from the Red Sox. I feel very lucky to have this relationship with the Red Sox. I'll keep this connection as long as I can, with the Red Sox. Whatever they want. I'll come back. The people that are close to me are really the people I work with, for the most part.''

Part of him dreads Wednesday, not because it's the last game of a disappointing season, but because it's the end of what he's done for the past two decades.

"I'm going to have to say 'Goodbye,' and that's tough, man,'' he said, "because I'm so emotional. New England means a lot to me. This is my whole life I've been here. I take great pride in being a Bostonian. And it's sad. I'll be back, but it's like...I hate finales. My heart is here. This is where I sprouted -- 1978, and the Yankees. That was big. This is where I made a name for myself.''

The Red Sox had offered an on-field ceremony for the final homestand, but Eckersley politely but firmly rejected that. He's thought some about what he'll say on his final broadcast.

"I'm just going to say as much as I can without being upset,'' he said, his voice choking some at the prospect.' "I just want to get across how much affection I have for this city and for the Red Sox. It's heavy, man.''

He thinks for a minute, fumbling for the words.

"It's not about saying the right thing,'' he said. "It's about feeling. I just want to make sure everybody knows how I feel. I don't have to be profound. I just want to say 'Thank you,'' for making me feel the way I felt all these years.''

___________________________

Some end-of-the-year award thoughts:

AL MVP: Since I'm voting for this award, I'll honor the BBWAA's request to not reveal my choice ahead of time.

AL Rookie of the Year: Julio Rodriguez. Baseball is fortunate to have so many talented first-year players, but Rodriguez stands above them all.

AL Cy Young: Justin Verlander. It would be impressive enough for Verlander to be this good at 39. What makes it more incredible is that he's coming off Tommy John surgery.

AL Manager of the Year: Terry Francona. Most saw the Guardians as the Central's third-best team. But that didn't take into account Francona's ability to get the absolute most out of his roster, all while battling his own considerable health issues.

NL MVP: Paul Goldschmidt. Goldschmidt, criminally underrated, leads the NL in slugging, OPS, OPS+, total bases, is second in RBI and tied for fifth in homers, all the while playing superb defense. Any more questions?

NL Rookie of the Year: Michael Harris. Harris looks like a future five-tool superstar, and barely edges out teammate Spencer Strider. Is the Braves player development system sick or what?

NL Cy Young: Sandy Alcantara. Six complete games? Almost 230 innings? In this economy?

NL Manager of the Year: Buck Showalter. He gave the Mets stability and credibility, whether they win the division title or not.

_____________________

It's become somewhat fashionable, relative to Aaron Judge's remarkable season, for some to make offhand remarks like: "Well, we all know that Barry Bonds isn't the real record holder...''

Excuse me?

Some 15 years after Bonds last stepped into a major league batter's box, we're still debating this.

Look: we all know that Bonds had considerable help in hitting 73 homers in 2001. And perhaps in a more just world, the 61 homers by Roger Maris in 1961 would be recognized as the true standard by which all home run records are judged.

But that's not how this works. Baseball didn't disqualify Bonds or his accomplishments. They're right there in the record books.

Denying that is to head down one very slippery slope. Do we start ignoring wins and Cy Young Awards for Roger Clemens? Do we strip teams of world championships because some (many?) of the key players were dabbling in PEDs?

Where does it stop?

I fully understand Roger Maris Jr.'s thoughts on the topic. He's got a vested interest in his father's legacy and struggles with the fact that, until the other night, every hitter who eclipsed his father's home run total (Bonds, Mark McGuire, Sammy Sosa) was linked to PED use. He gets a pass.

But for others -- writers, broadcasters, players -- to casually dismiss history out-of-hand is highly disingenuous.