There will be no major league baseball played on March 31.

For that matter, you may not see it return until May.

Having extended the deadline to reach a new collective bargaining agreement until Tuesday at 5 p.m., the major league owners and the Major League Players Association still failed to agree on a new deal, causing MLB to wipe out the first two series of the regular season. For the Red Sox, that means the loss of a three-game season-opening series at Fenway with the Tampa Bay Rays (March 31-April 3) followed by a three-game set with the Baltimore Orioles (April 4-7).

The cancellation of Opening Day because of a labor dispute is the sport's first since 1995.

If no further games are canceled, the Red Sox would then open the regular season at Yankee Stadium on April 7. But given the tenor of the talks, the animosity that marked the final day of talks and the removal of some urgency, it would surprise few for the impasse to continue for some time, threatening not just the first week of the 2022 regular season, but the entire first month.

Players have charged that a cadre of small-market owners would be only too happy to lose all of April, when cold weather and children still in school servces to depress attendance.

There had been some hope late Monday night into Tuesday morning that a deal was within reach. In retrospect, however, that proved far too optimistic, and seemed to be coming from just one side of the bargaining table. Intent on painting the union as intractable, MLB leaked the notion that a deal was close at hand, when in fact, there was a considerable gulf between the sides.

By controlling the narrative, the owners believed they could then point the finger of blame at the players if a deal couldn't be reached. Owners then made the final offer to the PA mid-afternoon Tuesday, only to have the union categorically and unanimously reject it.

Both sides then began leaving Roger Dean Stadium in Jupiter, Fla., where talks had been held for the last nine days. When the two sides will even meet again is unclear, but many in the game believe the game will now be shelved for some time. It's likely that both sides will regroup, further survey their constituencies and wait for the other side to cave.

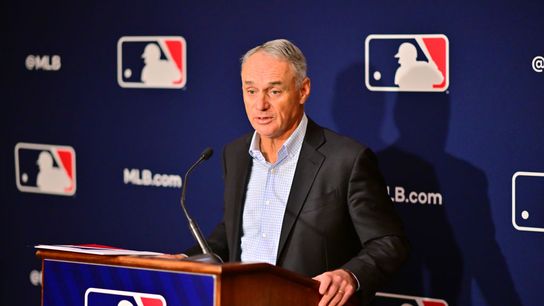

In a press conference, commissioner Rob Manfred, who had recently labeled the mere possibility of missing a portion of the regular season a "disastrous outcome,'' said the league "offered compromise after compromise'' and "exhausted every possibility,'' in an effort to reach an agreement. Manfred said the last offer to the union "offered huge benefits to our fans and our players.''

Meanwhile, in a statement, the Players Association, said the ongoing lockout, which began Dec.. 2, was "the culmination of a decades-long attempt by owners to break our Player fraternity.''

In the final days, some concessions were made on both sides, with the players willing to abandon their request to expand the pool of players eligible for salary arbitration. The two sides also agreed on a universal DH for both leagues, an expanded playoff system (from the current 10 teams to 12), and even began to tackle such on-field issues such as pace of play.

But while the sides got closer on such issues as minimum salaries -- with owners proposing $700,000 for 2022 with the players asking for $725,000 -- and other matters, they could not bridge the gap when it came to competitive balance tax (CBT) thresholds.

The Players Association wanted thresholds of $238 million, $244 million, $250 million, $256 million and $263 million over the life of a new five-year agreement, MLB offered only a modest increase from the 2021 mark of $210 million, with the first threshold at $220 million for the first three years, rising to $224 million and $230 million.

The incremental increase offered by MLB stood in contrast to the increased revenues the game has realized, to say nothing of the additional $150 million in new revenues coming from an expanded playoff format and advertisements on player uniforms.

That gap -- though there are others, including a huge one on pre-arbitration bonus pools, with owners proposing $30 million annually and the players at $85 million -- proved insurmountable and left the talks stuck, without further movement.

Manfred maintained that the games being canceled would not be made up, nor would the players be paid for games missed. There's also the matter of service time, which, should another two weeks worth of games be lost, could impact whether players get full credit for a year at the major league level.

That issue can still be negotiated in further talks, but for now, it stands as one additional obstacle to getting the game back on the field.