I'm usually loathe to make direct comparisons between one professional sport and another, because, frankly, it's often not a level playing field.

Among the major four North American sports, there's more that separates them than unites them. They have different fan bases, different economic models and different labor agreements. Comparing one to another can be disingenuous at best, and out-and-out irrelevant at worst. Oftentimes, you might as well be comparing apples to oranges.

But I'm going to make an exception here, because, in spite of what I just acknowledged, it's particularly apt in this case.

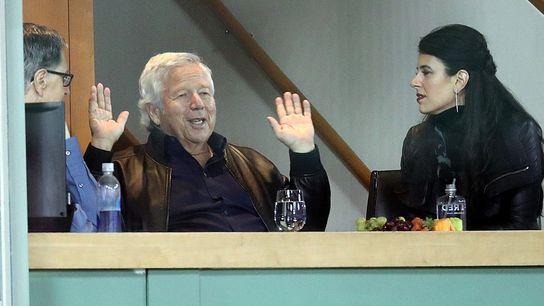

So, my question: Where is MLB's version of Robert Kraft?

The owner of the Patriots was instrumental in bridging the gap between the players and the owners the last time the NFL had a labor dispute. In 2011, with an impasse that had lasted several months in the offseason, Kraft helped broker a 10-year deal between the union and owners. (That he did so as his late wife Myra was nearing the end of her battle with cancer was even more remarkable). He reached a point where he couldn't sit idly by and watch the NFL self-immolate. He interceded with some common sense and it resulted in an agreement.

Jeff Saturday, then a player rep for the Indianapolis Colts said of Kraft: "Without him, this deal does not get done. He is a man who helped us save football and we're so (grateful) for that; we're (grateful) for his family and for the opportunity he presented to get this deal done."

DeMaurice Smith, the executive director of the NFL Players Association, echoed those thoughts, saying to Kraft: "We couldn't have done it without you.''

Surely, there must be a baseball owner with the determination and resolve to help solve the lockout, which is fast approaching its third month anniversary. But if such an owner exists, he's yet to reveal himself.

A handful of owners have been on hand for the week-long negotiations taking place in Jupiter, Fla. Ron Fowler of the San Diego Padres, Hal Steinbrenner of the Yankees and Dick Monfort of the Colorado Rockies have all been seen at Roger Dean Chevrolet Stadium, site of the talks. (Monfort is a known labor hawk, said to represent small-market interests, and as such, is ill-suited to play the role of mediator in these talks).

Mysteriously, Red Sox principal owner John Henry, who is a member of MLB's Labor Policy Committee, was supposed to attend these talks, but if he's been on hand, he hasn't been spotted. Henry owns a home about 40 miles away in Boca Raton.

Henry would seem to be a good candidate to serve as a deal-marker. He was once a small-market owner (Florida Marlins) so he understands the concerns of like-minded owners. And because he's been a free-spending big-market owner in Boston, he would theoretically have the respect and attention of the Players Association and its constituency.

Instead, the negotiations have been mostly steered by associate commissioner Dan Halem -- he's MLB chief labor expert -- and MLBPA's senior director, Bruce Meyer. Together, they've made -- at most -- incremental progress over the last three months.

Some new blood is needed, clearly.

Someone who is sick of the self-inflicted damage being done to the game. Someone with the foresight to find a middle ground. Someone who would immediately have the respect of both sides.

Someone like Kraft in 2011, who decided, even in his time of grief, that he couldn't stomach the prospect of a highly-profitable and hugely popular sport sabotage its way to a lost or shortened-season.

Kraft hasn't been perfect and the idolatry in which he's held by some members of the media (Note: his actual first name is Robert, and not, as some would have you believe, "Mister.") is a little much. But he's clearly done all that could be asked of a team owner; count the six championship flags waving over Gillette Stadium for further validation.

Maybe, just maybe, Kraft draws upon his experiences as a fan to help guide his actions as an owner. Kraft was a longtime (and long-suffering) season ticket holder in Foxboro before he bought the keys to the place, and it could be that those memories have helped him more closely relate to the fan experience.

(Henry, too, has his own distinct memories as a fan of the St. Louis Cardinals and Stan Musial, of which he's spoken repeatedly and fondly).

It doesn't have to be Henry who rides to the rescue. Though he has a long history of overseeing huge, successful transactions, he may not have the personality needed for such an intervention. Not every billionaire businessman is cut out for diplomacy and Henry is clearly uncomfortable in the spotlight. I can, however, assure you from some off-the-record conversations over the years, that Henry has some definite thoughts about the game's economic structure.

But somebody, somewhere, needs to emerge and rescue these talks.

It's certain that the role of 11th hero will not be played by commissioner Rob Manfred. Manfred injected himself into the talks Friday, requesting a one-on-one session with Players Association chief Tony Clark. But Manfred's role as a hired gun whose job it is to represent the best interests of the owners, precludes him from being the savior in these talks. The players don't trust him, and some of his ill-advised rhetoric over the years makes him especially unsuited for this role. (That's not necessarily a criticism of Manfred, either -- it's virtually impossible to imagine any commissioner with the ability to step in and save the day, with the possible exception of the NBA's Adam Silver. Silver has made it abundantly clear that he views the league's players as partners, and not adversaries, but that's a discussion for another day.)

Perhaps the dynamics of the sport have shifted too much to allow such a scenario. In the past, someone like former Toronto owner Paul Beeston would have had the trust of the players to step in. No such obvious candidate exists in the current environment, and it may be that either at Manfred's behest, or by their own agreement, the 30 MLB owners have made a determination that solidarity trumps all. In the past, the owners have been done in by division among their own ranks (with big-market owners vs. their small-market brethren representing the most obvious schism), and the need to remain unified is paramount.

By most objective accounts, owners finally managed to end their decades-long losing streak at the bargaining table in the last negotiations, so any suggestion that they change strategy is likely fall on deaf ears. For a change, the owners are on a relative roll and aren't about to jeopardize that.

Still, it would be nice to see someone, anyone, step forward, and show the same passion for a solution that works for both sides.

This much is certain: as bleak as it may appear this weekend, days before an MLB-imposed deadline of Monday in order for a full 162-game schedule to be played, a deal will be reached at some point. Maybe it's next week, maybe it's later in March. But at some point, there will be an agreement with which both the owners and players can live.

Why not find that now, when a full season can still be salvaged? And why not have it mediated by an owner who finds the current impasse to be every bit as distasteful and unnecessary as so many fans do?

Most of today's owners have realized enormous success in the business world. Some have regularly dealt with unions in doing so. Why not put that experience to use for the good of the sport, the way Robert Kraft did with football more than a decade ago?

_________________________________

In most years, it's an advantage being a young player added to a team's 40-man roster.

It signifies that the organization believes you have a legitimate -- likely, even -- chance of becoming a major leaguer. Spots on the 40 are precious and teams don't just give them away. If you're on a 40-man roster, it means you're that much closer to realizing your dream of making it to the big leagues, and probably soon.

Also, being on the 40-man means you're paid better than others in the minor leagues and realize higher per diems and living allowances in spring training. You also qualify for benefits like improved health coverage and union representation.

But this year, it's something of a double-edged sword.

There are about 10 or so players on the Red Sox' current 40-man roster who probably have next-to-no chance of making the major league club at the start of the season -- whenever that might take place. Either they need additional development time or their current position is blocked at the major league level, or both.

Jeter Downs, Jarren Duran, Connor Wong, Ronaldo Hernandez and Josh Winckowski all fit into this category. It's possible every one of these players could make it to Boston at some point in 2022 (Duran and Wong already have).

But in this Late Winter of Our Discontent, their presence on the 40-man roster actually works against them. For the purposes of the lockout, these players are no different than, say, Xander Bogaerts or Chris Sale. Bogaerts and Sale may have eight-figure salaries and All-Star accomplishments, but they can't legally work out at their team's spring training headquarters or take part in spring training games -- and the same is true for Downs, Duran et al.

When a deal is struck, there will be less time than usual to impress the organization's front office and coaching staff, because, in a shortened spring, the emphasis will understandably be placed on getting the likes of Bogaerts and Sale ready for the start of the MLB season. There will be fewer opportunities -- both in terms of games and playing time -- for the prospects.

And, in the event that the impasse drags all the way into April, those surplus 40-man players will have to report to extended spring training to get ready for their minor league seasons, already far behind when it comes to conditioning and game reps when compared to the likes of Triston Casas and others who aren't on the 40-man and will have had the benefit of a somewhat normal spring in order to be prepared for the start of the Triple A season.